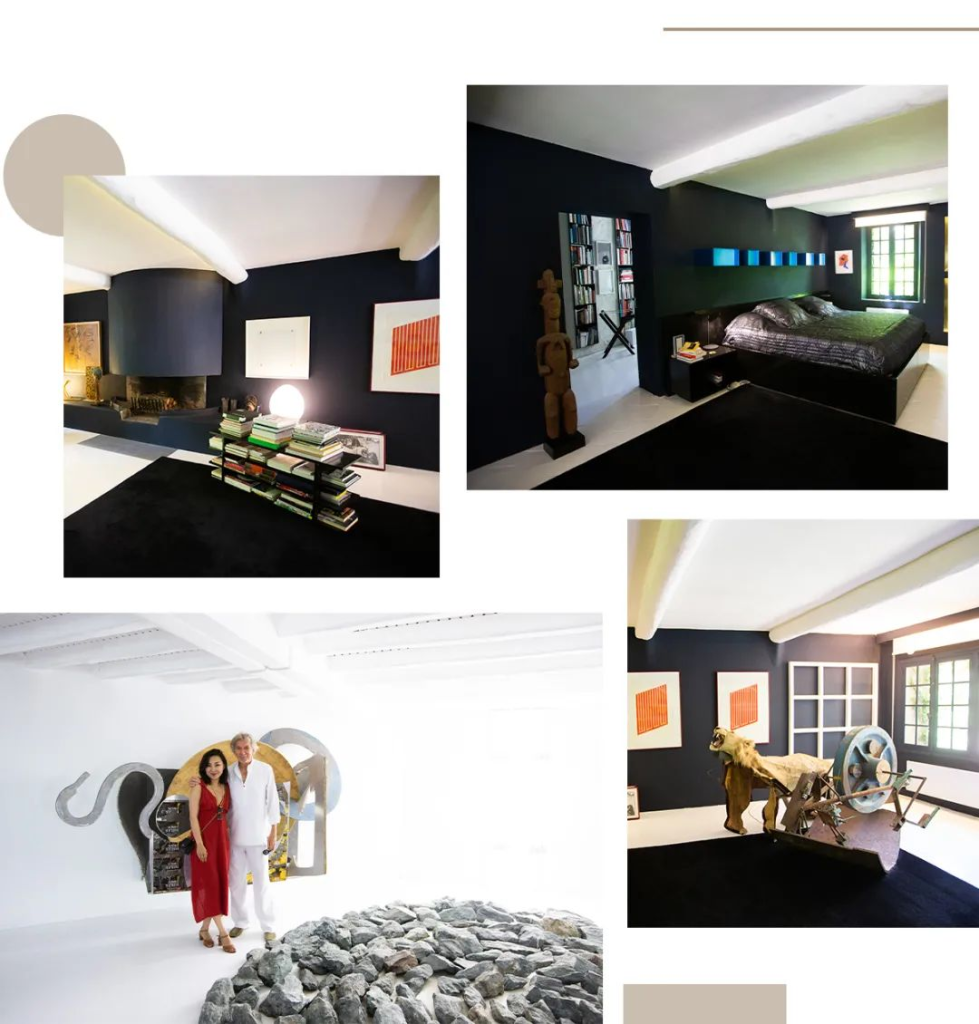

With Bernar Venet at his home in Le Muy

“Many people seek a ‘balance’ between life and work, but for me, it is only working that gives me that ‘balance.’ Working is the only way to make me feel alive,” the artist Bernar Venet told me when I visited his art foundation, the Venet Foundation, in Le Muy, South of France, last summer. As an artist who relentlessly pursues nuanced aspects of creation, in a constant state of advancing his limitations, Venet’s enormous energy prevents him from relaxing with a mind that is constantly working. He says, “Few people have the ability to realise the ‘unknown,’ and if they do, it’s fortunate, but it can be very exhausting.”

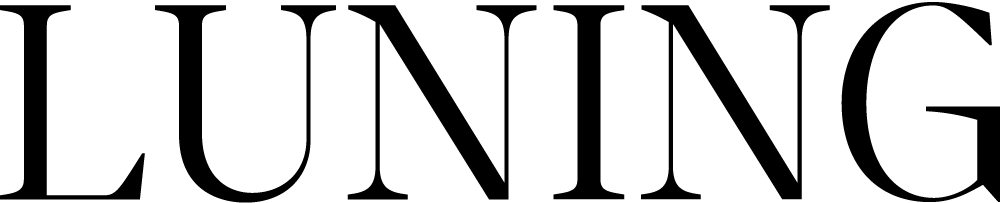

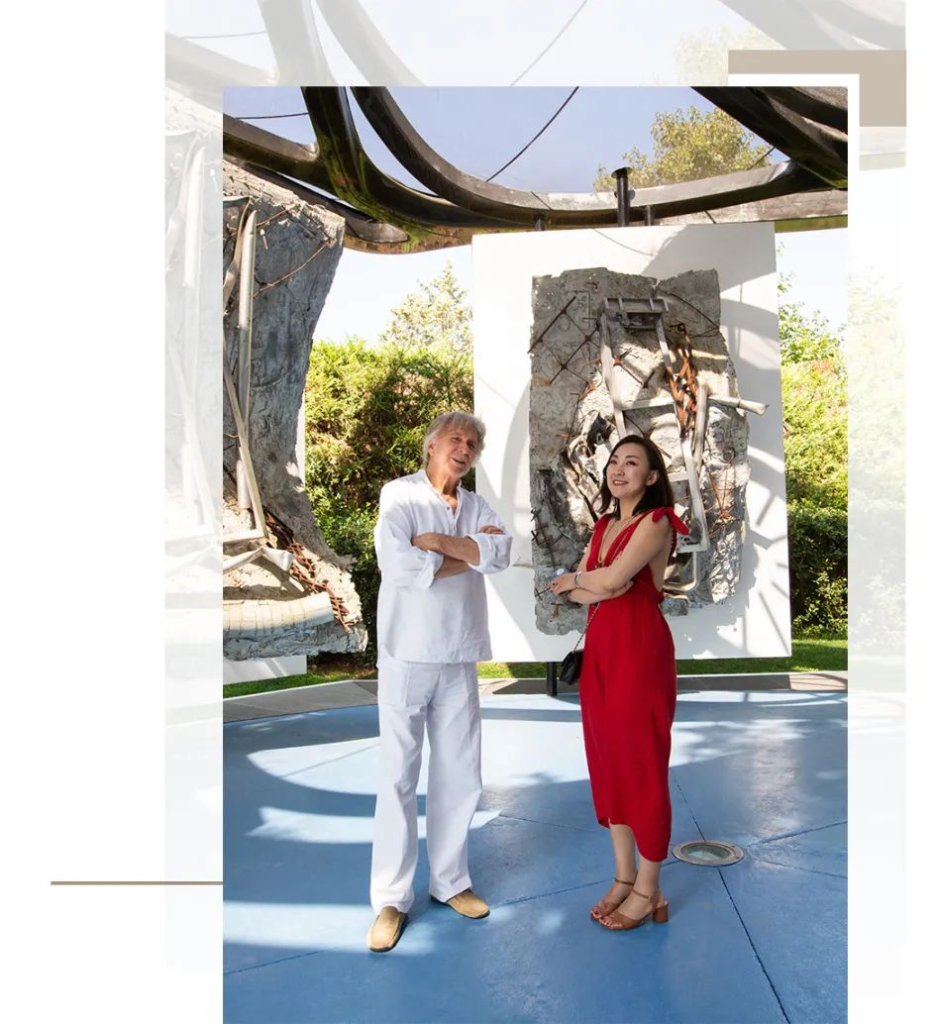

In front of Bernar Venet’s own sculpture at Venet Foundation

Even as an internationally renowned artist, with works in various institutional collections of note, his art housed in permanent exhibitions worldwide including the Palace of Versailles, and having been honoured with France’s highest order of merit, the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, Venet remains unsatisfied. His interest lies in the unprecedented, exceeding and transcending.

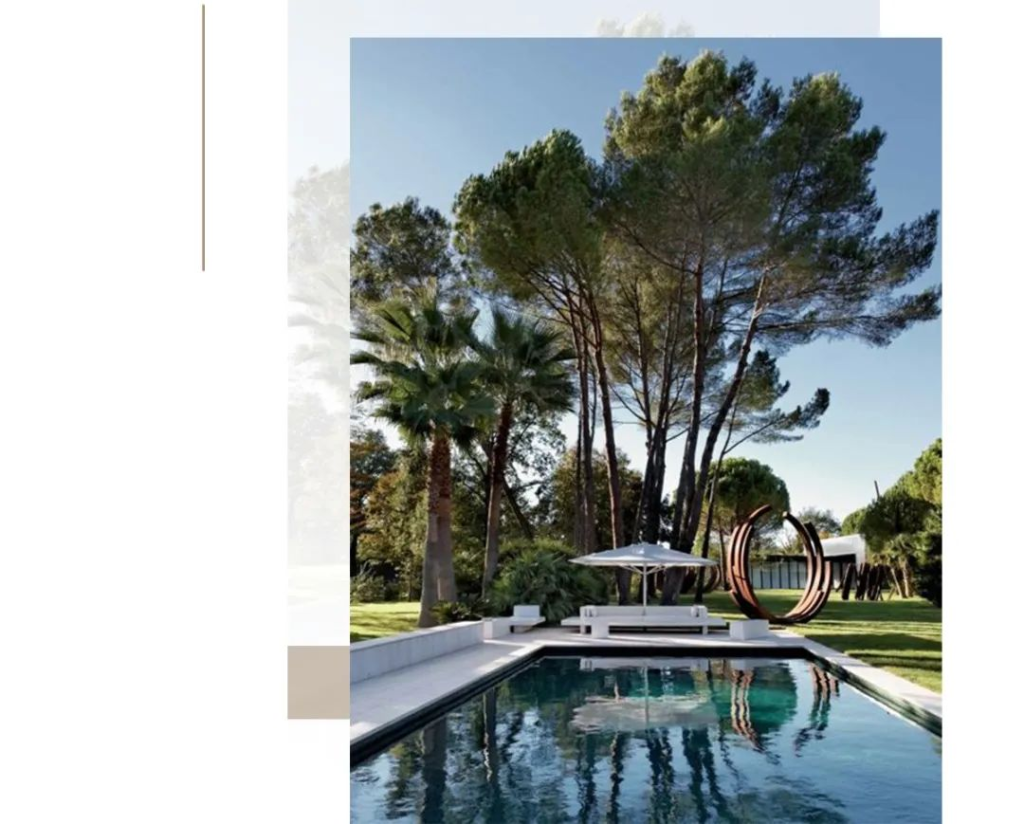

Today, Bernar Venet is well-known for centralising linguistic aspects of mathematics into his works, which are neither abstract nor figurative. His large-scale minimalist sculptural works are renowned, presenting an array of straight lines, arcs, angles, and indeterminate lines in corten steel.

The majestic forms of Venet’s sculptures, imbued with philosophical thought, present an incredibly sexy first encounter. They possess an almost tactile, visceral quality which resonates within you as the viewer. By understanding more about Venet’s artistic process and hearing him speak about dreams and visions, we can understand a sense of urgency in his work. There is less ‘self-reflection’ in his art; the works are a realised form of his need to channel his vision, exceed his limits, and transcend his capabilities—a materialisation of his process of asking himself “why not?”

Venet’s monumental sculptures around the world

When Venet has an idea, he will simply go ahead and conceive it. It is this determination that has enabled him to create many works that could be considered inconceivable by others. As a man who is constantly in pursuit of excellence, he never likes repeating himself, preferring to create works of historical significance and remarkable ingenuity.

Venet believes that his success was originally determined by the luck of being in the right place at the right time. Moving to New York from the South of France in the 1960s, Venet’s arrival coincided with the origins of the minimalist movement. He moved in these circles, amongst like-minded artists, in the heyday of a collective now documented in art history books. Despite their minimalistic tendencies, they were maximalists in their lives; Venet danced with Rauschenberg, dined with Rothko, went clubbing with Donald Judd, found Sol LeWitt a girlfriend, and saw Jasper Johns crying because of an existential crisis.

Although these stories are now only distant memories for Venet, the tales of his friendship with those historic artists exert magic that captures our hearts and imagination. As a man who proclaims to have no attachment to the past, Venet’s curatorial conception, his art foundation, is a veritable cornucopia of artworks from both the past and present.

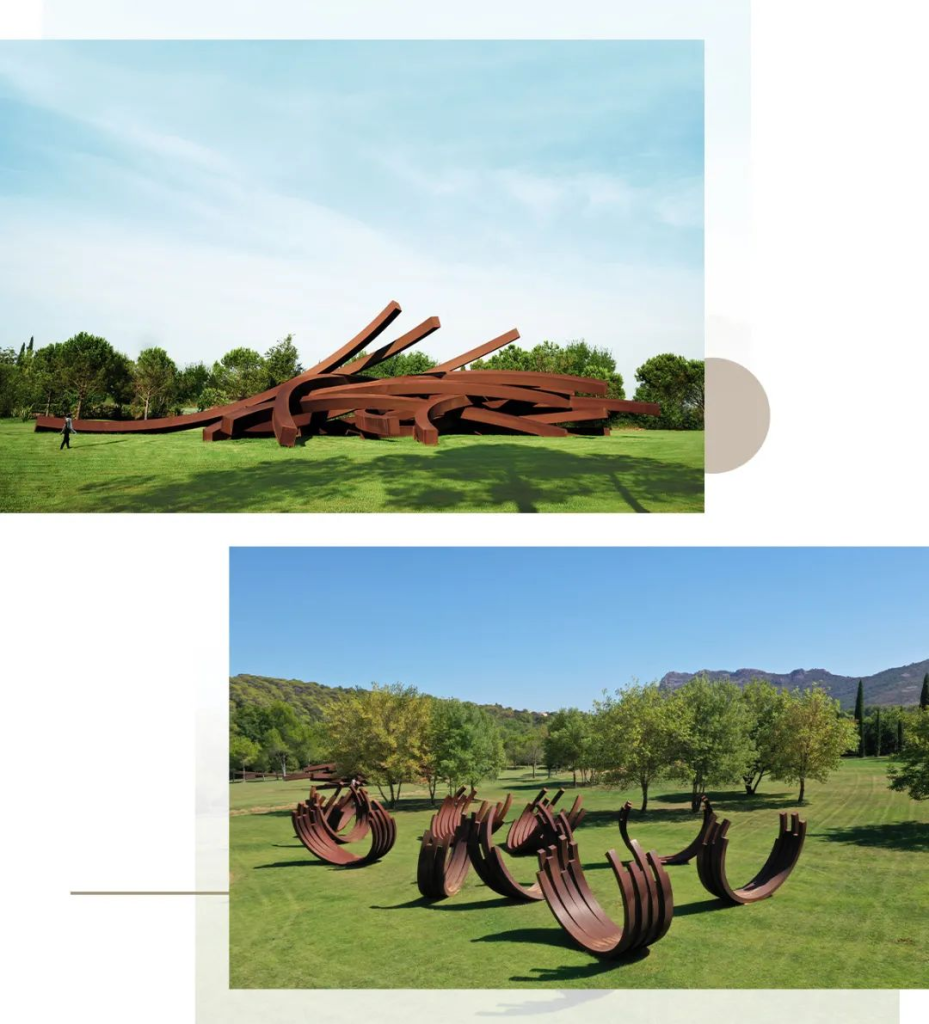

View of the Sculpture Park with James Turrell, Elliptic Ecliptic, 1999

Venet Foundation was founded in 2014 by Venet and his wife Diane in Le Muy. Before that, they spent 25 years in constant renovation and expanding the land. The 17-acre foundation has preserved the rustic nature of Les Serres in Le Muy, which is nestled amongst hills and mountains. Entering the Foundation is like walking into a paradise, removed from the outside world; you are greeted with birdsong and the distant sound of a waterfall and can’t help but wonder if you ever have to leave.

The pool, signed by Francois Morellet, with the New Gallery and sculptures by Bernar Venet in the background

The sculpture park on the grounds of the foundation showcases Venet’s large-scale monumental works as well as a collection of work by his contemporaries and friends. The Venet Foundation was very much inspired by the Donald Judd Foundation in Marfa, Texas, which integrates the contextual life and work of other artists. Besides its permanent collection, Venet Foundation also houses a library and archive, along with an array of exhibition programmes. Venet aimed to make his foundation a “total work of art,” which in his own words, “acts as a faith, it shows my own personal journey and art history, also my accomplishment. You can know everything about me when you come here.”

Venet sculpture park

Besides “historical relevance,” an important criterion for Venet’s curated collection centres on tracing both his own artistic journey and affiliation with art movements alongside reflecting on his personal relationship and friendship with his contemporaries. Rather than drawing on a wide range of historically significant artworks, as some art foundations have done, the Venet Art Foundation focuses on works by a variety of artists from the French neorealism, minimalism, and conceptual art movements, with a focus on American and French conceptual artists. Venet isn’t interested in purely ‘beautiful’ works; he says, “I am not decorating my garden, but adding humanity to culture.” Thus, we can see his sculpture park filled with historical works by conceptual and minimalist artists. This collection includes a specially commissioned “chapel” by Frank Stella, James Turrell’s Elliptic, Ecliptic, the world’s largest outdoor installation by Larry Bell, a major Anish Kapoor, and a swimming pool conceived by Francois Morellet among others.

James Turrell (above) and Larry Bell, Something Green

Venet has hundreds of artworks and objects at his house situated on his foundation; they not only show a particular chapter in art history but highlight his personal taste as a collector, as well as each being embedded with many anecdotes about his relationship with these artists. Many pieces at home were works created for him by friends or that he exchanged with those artists. In his living room, he has a neon sculpture created especially for him by Francois Morellet, a gravity-defying felt sculpture by Robert Morris, a stone-stacked geomorphic artwork by Richard Long, and a transparent ‘trash can’ filled with non-perishable waste by Arman. In Venet’s bedroom, a kinetic lion work by Jean Tinguely, de Kooning’s charcoal work ‘Woman’ and at the centre of it all, a work which Venet and his wife sleep on—a bed conceived by Donald Judd. Venet jokingly told me that he secretly wished to have seduced Judd’s wife to the very bed.

Bernar Venet home, Donald Judd bed and Jean Tinguely sculpture in his bedroom

The remarkable collection of art, the breathtaking view of Le Muy, and the fascinating stories told by Venet about his artistic journey, together illustrate a life which many people do not dare to dream of. Many people spend their lives thinking about doing something else or living elsewhere but never pursuing it. I asked if Venet could offer any tips to those who wish to live their lives in the same way he does, a life which can transcend one’s imagination. Venet said that is something one could not give any advice on, the courage to pursue what we want in life and how we live our lives really comes down to a person’s internal drive and personality, which is mostly something you are born with.

Bernar Venet home, Richard Long, Frank Stella, Robert Motherwell and Lawrence Weiner site-specific works

However, I believe experience can also shape a personality. Listening to Venet’s stories, I realised his own experience made him a person with a lot of gratification. He talked about the importance of “luck” and “timing.” Being born into a family of teachers and physicists, the youngest of four children, whose mother knew nothing about art but gave her son her full support when he showed an interest in it. Venet recalled how he was unlucky to not be accepted to the art school in Nice, but then called it pure luck, for if he had been accepted, he would have had four years less to study. He gained four years of his life that he would have spent studying. Because he was unsuccessful in being accepted, he was able to complete the equivalent of four years at art school in one year by himself.

Venet’s living room, Francois Morellet

Following his rejection from Nice, Venet joined the army. It was during these years that he was lucky enough to have his own art studio there. He later met the artist Arman, who sponsored his flight to New York and opened a whole new world for him. Recognising the power of luck in his life and career, Bernar Venet continues to emphasise the need for lucky people to take responsibility and give back to society: “I became wealthy because of my art, so I will give back to society and to art itself with the wealth I have accumulated.”

With Bernar Venet at the Stella Chapel in the Sculpture Park

For such a determined person like Venet, it’s easy to believe that he has never stopped in his life, but in fact, he did stop—for six years in the 70s, he did not make any art. Venet told me it was logical for him to stop at that point in time—at a certain moment, he felt detached from the works he was exhibiting, he was making no decisions for himself, he was made to go against his own ‘subjectivity’ by allowing the objectivity of other people who were controlling his process. He didn’t want to lapse into a pattern, befallen by many, where an artist who has achieved a certain level of fame and recognition is fated to repeat themselves.

An artist is different from a teacher, who uses other material to disseminate knowledge. An artist needs to create their own material and language. Eventually, an artist needs to make their ‘subjectivity’ an objective reality and transcend their own limitations. When Venet stopped making art for six years, he did not stop pursuing art. His six-year pause only added to his determination to both create and succeed. Recalling his comment where he attests that it is “only through work, that can I justify living,” he takes the ‘live to work’ adage to a new level and proves his strength and resilience will not stop at any point in his life and career. Venet’s conviction destined him for greatness; his desire to transcend bodily and societal limitations is materialised in his work, and there is truly no stopping him. I wouldn’t put any limits on Bernar Venet. However, he would enjoy the challenge—perhaps we will see more of his sculptures at unpredictable and extraordinary places in the world over the coming years, the Great Wall of China? Maybe.

-the end-

Text: Luning

Copyediting: Rosie